Who is this guideline for?

This set of guidelines are intended as a primer for life scientists that would like to reuse the HiFi assembly workflow in this repository.

The guide is split between the 3 core elements of the workflow: these being pre-assembly quality control, assembly and post-assembly quality control. We have included useful explanations, background and links to further information throughout the guide.

Accessing this workflow

This workflow is:

- currently operational on the Gadi HPC at the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI),

- registered on WorkflowHub,

Stage 1: Adapter filtration and pre-assembly quality control

Overview

De novo genome assembly is a complex analysis process. Adapter decontamination is very critical step in genome assembly. In this pipeline, adapter filtration through HiFiAdapterFilt is an optional step that can be enabled through the parameter --adapter_filtration. In case adapter filtration is enabled, the remaining steps in the pipeline will use the output of this step instead of the original bam files.

It is also important to assess the raw sequencing reads prior to de novo genome assembly as genomic characteristics are hidden in the fragmented reads. A common QC step is to use k-mer frequencies of the raw reads to profile the genome. This pre-HiFi genome assembly QC module aims to allow you to confidently estimate major genome characteristics such as genome size, heterozygosity, and repeat content based on the k-mer distribution in the reads. GenomeScope is a good tool for this pre-assembly QC step and this document will explain the details of the results generated by GenomeScope.

Background

Each species’ genome carries distinctive properties, like genome size, heterozygosity, ploidy, GC content and genome complexity. These fundamental properties have a significant impact on quality and cost for every genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation project.

Genome size estimation

For any genome assembly project, the starting point is sequencing the desired genome. It’s important to estimate genome size prior to sequencing to decide how much sequencing is needed. The sequencing depth, coverage or amount of sequencing greatly depends on genome size (see June et al. 2020. Therefore, genome size estimation is the top priority. Traditionally, flow cytometry and k-mer frequency distribution are used for predicting genome size.

To estimate genome size, you can use one of 3 approaches:

- Flow cytometry is an experimental, dye-based technique that provides rapid multiparametric analysis of nuclear DNA. Its popularity lies in the ease of preparing and processing large sample cohorts in a short period of time. It is also fast and robust.

- K-mer frequency distribution is a computational method that estimates genome size using average k-mers abundance. Mathematical models like negative binomial distributions or poisson distributions are used to fix the histogram of distinct k-mer frequencies. These k-mer counts can also be used to infer repeat content, sequencing coverage, sequencing error rates and heterozygosity.

![]() WARNING: there are limitations to the K-mer approach, it requires a significant amount of sequence for genome size estimation.

WARNING: there are limitations to the K-mer approach, it requires a significant amount of sequence for genome size estimation.

-

C-value estimation of genome size. The DNA amount (pg) in the unreplicated gametic nucleus of an organism is referred to as its C-value, irrespective of the ploidy level of the taxon. There are different C-value databases for different species. If the sequencing species is not available, a close relative will provide a good estimation.

- The 3 popular C-value databases are:

- For animal genomes: http://www.genomesize.com/

- For fungal genomes: http://www.zbi.ee/fungal-genomesize/

- For plant genomes: https://cvalues.science.kew.org/

- The 3 popular C-value databases are:

As genome characteristics vary drastically from one domain of life to another, it is highly recommended to use both approaches (i.e. flow cytometry and k-mer methods). These are the gold standard for genome size inference.

Heterozygosity, ploidy, and repetitiveness

Heterozygosity, repetitiveness, and ploidy also play a crucial role for a genome assembly. It is usually recommended to use a single individual, isogenic lines, or a highly inbred diploid organism for sequencing. This will help in minimising potential heterozygosity problems during genome assembly for short read technologies.

Note:

- It’s not possible to use isogenic lies while working with eukaryotes.

- It would be wise to have a knowledge of the sex-determination system of the organism you are sequencing (eg XY, ZW, XO, sex reversed) and whether it is best to sequence a male or female with preference for heterozygous sex.

- Long reads will be able to handle the typical repetitive elements (transposons, retrotransposons etc) as the reads are longer than the typical element (assuming the library is of good quality) but will struggle with long segmental duplications.

- Known sex of the organism is useful.

- Use of polyploid or less inbred samples may increase the number of alleles present, thereby resulting in a more fragmented assembly or producing uncertainties about the contig homology. Presence of highly repetitive regions may also complicate genome assembly. The assembler may confuse or fail to distinguish very similar regions. This may lead to misassembly and thereby misannotation.

Initial estimates of genome size using karyotyping or other methods may not factor in genome complexity. This means that 50 - 100% more sequencing might be required for polyploid and highly repetitive genomes. Thus, understanding genome characteristics before analysis is an important step in any assembly project. It also helps to assess whether the generated sequencing data is sufficient or more required.

General recommendations for HiFi read pre-assembly QC

In general, HiFi reads are ready for downstream analysis without any QC tool needed. Adapters are trimmed on the instrument and CCS will ensure that most of the sequencing noises are removed.

Note:

- It is important to keep the subread data. Lower quality reads (including those with not enough passes) should be retained. These can be used to fill gaps after scaffolding.

- The instrument base calling may miss the adapter very rarely, but it should not do that in multiple passes as the error rate is random. In case of missed adapter calls, it should get eliminated during the CCS process. However, for sanity check, blasting the adapters would help to identify contamination.

The 4 recipes of success for a good assembly at pre-QC stage are:

-

Coverage: Make sure there’s enough coverage: usually 10X to 15X per haplotype is recommended for building a haploid assembly. This is based on empirical evidence suggesting that this is sufficient coverage, but also, by Poisson distribution properties. i,e, for obtaining a minimum of 4 reads for 99.99% of the haplotype, one would have to sequence that haplotype to 13X coverage. Note that the current phased genome assemblers can only operate on diploid genomes.

-

Read length: A good length library is also a factor for a successful assembly. The ideal read length depends on the repeat content of the genome. This knowledge usually comes from looking at a related species that’s been sequenced, as these will typically give you an idea of repeat length. Studies on rice showed that the average read length was > 15 kbp. For humans, 13kb would usually be sufficient because it would easily span over dominant transposable elements. However, the length of transposable elements can’t be determined for unknown species. Therefore, 15+ kbp is usually a good guide across organisms when doing de novo genome assembly. Again, there is no hard and fast rule; this is an empirical observation.

-

Quality: Usually you should aim for a median quality of Q28 for the full dataset. Most of the time a HiFi library around 15-20 kbp should generate around Q30, and so if you have Q27, you may suspect that the library may not have been great to begin with. It may still give you a good assembly, if there are enough high accuracy reads to cover the genome. For instance, the general consensus is that nanopore reads are less in quality compared to pacbio reads. However, a very high coverage of nanopore reads may give you a better assembly than an assembly using pacbio reads with less coverage. Quality is important, but at times can be overcome by increased coverage. Note: Base calling accuracy is measured by the Phread quality score also called Q score. Essentially, it indicates the probability that a given base is incorrectly called by the sequencer.

-

K-mer characteristics (see theory): For genome assembly you can also use k-mer tools traditionally meant for short-reads such as GenomeScope to inspect the k-mer characteristics such as genome size, heterozygosity rate and repeat content from unprocessed reads. HiFi reads are accurate enough so any k-mer tools work well with HiFi reads.

Genomescope

One of the popular tools that can be used for pre-assembly QC is Genomescope. It uses an equation that accurately models the shape and size of the K-mer graph using four negative binomial peaks whose shape and size are determined by % heterozygosity, % sequencing duplication and % sequencing error. These are all very useful pieces of information to help you learn more about your genome based on the raw data. Many tools are available for K-mer frequency estimation such as:

Genomescope is an R script that uses k-mer frequencies generated from raw read data to estimate the genome size, abundance of repetitive elements and rate of heterozygosity. This tool is made available on Galaxy Australia, is listed on bio.tools and the documentation for use is available here.

Interpretation of the GenomeScope profile graph

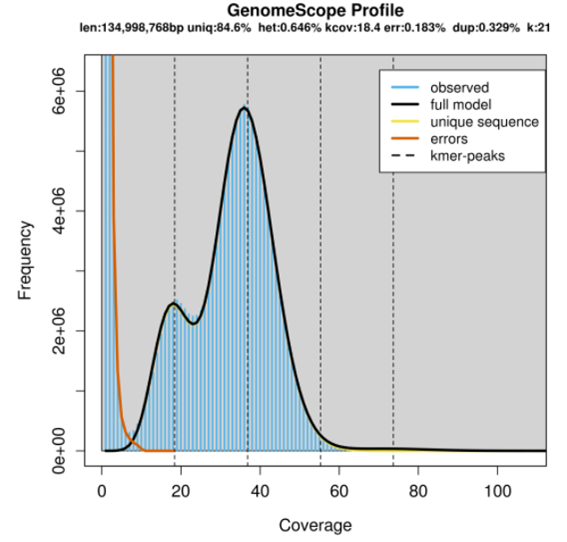

The image below presents an example GenomeScope output of the 21-mer profile:

Note: Coverage, heterozygosity of samples and the size of k-mer influence the outcome.

It is a general practice to use an odd number k-mer with three different sizes for a genome assembly. However, it is not required for genome size estimation using GenomeScope. A 21-mer profile is suitable in this instance because:

- K-mer 21 length is sufficiently long that most k-mers are not repetitive,

- Short enough that the analysis will be more robust to sequencing errors, and

- Only very large genomes with haploid length greater than 10GB may benefit from a higher k-mer value

The summary result shows (below the graph title):

| Label in figure | Meaning | Value |

|---|---|---|

| len | Estimated genome size | ~134Mbp |

| uniq | Estimated unique region | 84.6% |

| err | Error rate | 0.183% |

| het | Estimated heterozygosity | 0.646% |

- The large number of unique (near unique) K-mers that have a coverage of 1-7 (the extreme left side of the graph) is due to technical and/or biological variables (orange line in the graph). The technical errors or sequencing errors, can be amplification biases of certain genomic region during PCR especially for Illumina sequencing. The biological variability can be the presence of repetitive sequences in the genome.

- The big peak at 36 coverage in the graph above is in fact the homozygous portions of the genome that account for the identical 21-mers from both strands of the DNA.

- The dotted line corresponds to the predicted centre of that peak.

- The small peak/shoulder to the left of the peak corresponds to the heterozygous portions of the genome that accounts for different 21-mers from each strand of the DNA.

- The two dotted lines to the right of the main peak (at coverage = 54 and 72) are the duplicated heterozygous regions and duplicated homozygous regions and correspond to two smaller peaks. The shape of these peaks are affected by the sequencing errors and sequencing duplicates.

Stage 2: Assembly

Overview

The newer version of Pacbio Sequel II outputs highly accurate long reads (also known as HiFi reads). This offers an exciting opportunity for non-model genome assembly projects, as the HiFi reads are of sanger quality accuracy (>99%) with longer read length. There are many tools available for HiFi assembly (see below for more details), one among them is Pacbio developed ‘improved phased assembler’ [1] (IPA). This assembler provides high contiguity with fully phased haplotigs. Compared with Falcon and falcon unzip this has better processing time and high phase accuracy.

This presentation provides details about IPA along with comparing performance with other assemblers.

Sample output

The assembler mainly outputs two fasta files:

- one is primary contigs, and

- the other is associated contigs

Other HiFi assemblers

You could replace IPA in this workflow with one of the other HiFi assemblers.

For example:

Stage 3: Post-assembly quality control

Overview

The advent of high throughput long read sequencing technology, coupled with a decrease in sequencing cost has accelerated the creation of non-model eukaryotic genome de novo assemblies. Many genome assemblies are now made available on public repositories (such as NCBI Assembly) and are being published on a daily basis. Each assembly study may use different sequencing technologies, with varied read length and sequencing quality. The studies may also employ diverse assembly algorithms and workflows. Evaluating the quality of the assemblies for any downstream analyses and biological interpretations is therefore vital. Here, we include a brief description of the software implemented to evaluate assemblies produced by our HiFi assembly workflow.

Background

It is essential that researchers aim for a high-quality assembly: a good example is the human genome GRCh38. However, it is not always possible to achieve reference quality: a result of various technological and procedural limitations. However, we can still evaluate the quality of assembly. A good assembly depends on the contiguity, correctness, and completeness.

Contiguity

The basic function of a genome assembler is to process reads (i.e. sequences) to generate larger fragments, generally called ‘contigs’. Traditionally, statistical methods are applied for evaluating contiguity. This tells us how many contigs are generated (N), the minimum contig length that represents half the genome size (N50), and provides a summation of the number of contigs that contain more than half of the assembly size (L50). There are many tools that can provide these values. Here, we implemented Quast (see also Gurevich et al. 2013) software to calculate these values for an assembly.

Completeness

Though the contiguity metrics gives a technical summary of the genome assembly in terms of scaffold continuity and other related metrics, it lacks biological interpretation. Completeness can also be used to evaluate the quality of the assembly. One popular way to measure completeness is by comparing with known or existing datasets that contain single copy marker genes. Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO, see also Waterhouse et al. 2018) provides a summary of complete single copy, duplicated, fragmented and missing orthologs. This provides a quantitative measure of the genome completeness in terms of expected gene content.

Correctness

The completeness (BUSCO) metrics provide a summary based on known or existing ortholog gene markers, which are usually less than one percent of the genome. It does not tell us about the other parts of the assembly and how accurately they are stitched. Measuring correctness, helps to generate a reference quality assembly, but is also quite challenging. If a pre-existing reference exists, then a simple alignment can give a fair idea of the correctness. However, this is not the case with most de novo assembly projects: often they are non-model organisms that do not have any reference. Some methods proposed for measuring correctness include assessing frameshifts, comparing with high confidence regions of same or related assemblies, exploring bac comparisons and estimating error counts. All these methods do require additional datasets or short read sequencing. Users can determine the most appropriate approach, depending on data availability and resource [3].

Quast sample outputs

Quast produces output metrics in various file formats, including tsv, tex, txt and even a html report with icarus view. Below is an example set of Quast metrics showing no. of contigs at various length thresholds, largest contig size, total length of the assembly, GC%, N50 and L50.

BUSCO sample outputs

BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) provides measures for quantitative assessment of genome assembly, gene set, and transcriptome completeness based on evolutionarily informed expectations of gene content from near-universal single-copy orthologs. Busco produces various output files and folders, including busco sequences, HMMER output of searches with BUSCO HMMs and predicted genes.

The following link provides a detailed BUSCO results interpretation: https://busco.ezlab.org/busco_userguide.html#interpreting-the-results

References

- Jung, H. et al. Twelve quick steps for genome assembly and annotation in the classroom. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, 1–25 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008325

- 2020, G. A. W. No Title. https://ucdavis-bioinformatics-training.github.io/2020-Genome_Assembly_Workshop/kmers/kmers.

- Sović, I. et al. Improved Phased Assembly using HiFi Data. (2020).

- Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086

- Waterhouse, R. M. et al. BUSCO applications from quality assessments to gene prediction and phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 543–548 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx319

Appendix

Appendix A: K-mer frequency theory

As previously discussed, K-mers frequency can help to estimate biases, repeat content, sequencing coverage, and heterozygosity. Here we discuss the theory briefly [2].

“K-mers” represents, sequences of length K. For a given sequence of length L, and a k-mer size of k, the total k-mer’s possible will be given by:

( L – k ) + 1

To get the actual genome size, we simply need to divide the total by the number of copies:

n = [( L - k ) +1] x C

N = n / C

L = sequence length

k = k-mer size

C = copy number

n = total no. of k-mer’s for length k

N = actual genome size